I started writing this piece a couple of years ago, but never finished it, because I think it felt like a hopeless enterprise, given the way things are in Australia. Maybe it still is, but here goes.

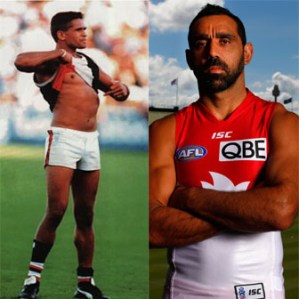

When the Adam Goodes thing was happening, I was sickened and horrified, not just by the booing, but by the seeming inability of the average punter to see this as racist intimidation. I remember reading a thread on our local Facebook Community noticeboard at the time, where someone I know and like had branded Goodes a “sook and a dobber”. This bloke, like so many other people, was unable to see that calling an Aboriginal man an ape, and then bullying him for objecting to it was racism, pure and simple. Even though I understood that neither the 13 year old girl at that game, nor the average person has an awareness of the historical significance of calling a black man an ape, it wasn’t this ignorance that caused me so much despair during this period. What really distressed me was the fact that, as a white Australian, raised in Australia, I knew exactly why the crowds had turned on Goodes.

Around the time that this was happening, I met a bloke from New Zealand who had just taken over as CEO of a big Australian company, with lots of staff. We chatted for a while about the concerns of managing a big team in a new country, and then I asked him: “how are you coping with all the racism?” He was a bit reluctant to say anything uncomplimentary about Australia, but finally admitted “I’ve never come across anything like it.” He was surprised that, as an Australian I was aware of it, but what he didn’t realise was that, just like a “magic eye” picture, my own endemic racism had slowly revealed itself to me over a number of years. This elemental and sinister thread snakes its way into the hearts and infects the minds of young Australians from a tender age. One of my earliest memories was hearing my beloved kindy teacher in Kalgoorlie advising us solemnly not to drink out of Paddy Hannan’s fountain, “in case an Aborigine has drunk out of it before you.” Comments like this have an impact on children. You don’t actually have to sit a child down and tell them things about the world for them to get the tip, and the tip I got was, Aboriginal people are not your mates, they’re not people you hang around with, essentially, they’re not really real people.

This unconscious belief finally bubbled up into my awareness when I had my first baby. I was 26, and up until then had been oblivious to the fact that I lived in a country whose original inhabitants were now invisible at almost every level of society. I happened to be alone for a night while my husband drove the vegie truck to Perth, and was watching a program about the Stolen Generations. I remember thinking afterwards, “God, imagine living in a country where someone could just walk in the door, and take your baby from you.” Then I realised I did live in that country. This was my country, and this happened to people here. The force of this realisation hit me so intensely, that I actually grabbed my baby and frantically began looking through the dark windows to the outside, closing the curtains, locking the door and thinking about places to hide. It was at that moment that I realised I had never once, ever considered how the mothers of those snatched children must have felt. If I had ever given it any thought at all, I might have told myself that maybe it was “for the best”, unaware of the shameful belief supporting this: that these mothers “didn’t feel the same way as us.”

It’s very hard to explain how otherwise, kind, well-meaning people can collude with the wholesale cultural erasing of an entire group of people. Maybe it’s “because of our convict streak,” to quote the inimitable Dave Warner, but facing your own racism is an incredibly painful and shaming feeling, and I completely understand why it’s so hard to do. Nobody likes to reflect on their own cruelty or indifference, or even their ignorance. One of the reasons that Australians struggle to understand other cultures, is because they don’t recognise their own. If you think culture is something that only belongs to people who wear “funny “clothes or worship in strange places, try skiting about how much money you make, or arriving at a barbecue without a bottle of wine and with an empty plate as so many hapless newcomers have done when asked to “bring a plate.” Just as accepted cultural standards are invisible, so too are cultural taboos until you try and break one, and the biggest cultural taboo we have as white Australians is accepting what has been done to black Australians.

Despite the AFL’s recent apology to Adam Goodes, it’s clear that they still don’t really get what the problem was. Their ham-fisted implementation of the “booing police” simply underscores that they think that booing and bad sportsmanship was the reason for Goodes’ distress. Adam Goodes believed that in the 21st century, given the history of the eugenics movement and the origins of the Holocaust, no black man should be called an ape or a monkey. His faith that this was a reasonable expectation in a fair and just society was tragically misplaced. Instead of giving Adam Goodes the immediate backup this incident deserved, he was left to stand alone and fight alone, until he couldn’t fight any more. The minute that this targeted booing started , the AFL should have instructed every player in every team to sit down on the pitch until it stopped, in every game.

This did not happen because we expected Goodes to do what we demand of Aboriginal people every year on January 26th: suck it up princess, we won, you lost, it’s time to parrrtayy!!!

Australians pride themselves on being fair-minded, kind and warm-hearted, which just makes this level of callous insensitivity so hard to reconcile with our national character. Sadly, I think we still have a long way to go.