Author: gayb63

Old days, old ways

Old days, old ways

If there’s one thing I really love, it’s the way that the words and deeds of dead people get handed on through the generations, even when people no longer remember who said what. I find it so amusing that my kids will say things like: ”I must congratulate you-much as I hate to, I must.” They don’t know that these were words that my Mum and her siblings unfairly attributed to their maternal grandmother who was apparently a bit grudging in her praise. My kids have naturally never met their great-great grandmother, but it’s amazing that this joke has survived for so many years beyond her life.

Grandparents can be incredibly influential people, often more than they realise. My Dad’s mother was an amazing person, mother of 9 boys and 2 girls, ferocious rather than feisty and hilarious to boot. She was raised very hard by a strong and brave mother that she idolised, and a feckless, selfish father of convict descent, whom she despised. She and her sister Mary wrote a poem about him when they were children, which finished with the charming line:

“And when gets down into hell,

there’ll be some lovely burnings.”

Such gruesome horrors were certainly not a feature of my sheltered childhood, so Granny’s gleeful harshness held a particular fascination for us. We vied for her attention and longed for her to think of us little cream puffs as tough, strong and capable, which rarely happened. The only one of us who consistently got her approval was my older sister Sue who was referred to as “The pick of the bunch.” There was no room in Granny’s world for worrying about impartiality, or giving every child a prize to prop up their self-esteem.

I guess that’s why a couple of small incidents stand out for me, in looking back at this crucial relationship. Until the nursing home she was sent to in the last few weeks of her life cut off her hair into a “manageable bob”, Granny wore her long white hair plaited and pinned to the top of her head, using old-fashioned hairpins. I remember one Christmas or birthday when we presented her with the usual talc-and-nightie, I had for some reason also chosen a packet of hairpins. It so happened that she had just run out of these useful items, so when she opened the present and exclaimed: “hairpins! That’s exactly what I wanted!” , I glowed with pride and pleasure at being the chosen one, for that moment at least.

The other incident has had a longer lasting and surprisingly far-reaching impact. Granny was a famous cook, but in her last 10 years of life, was very restricted by bad hips, which meant that she always walked with a stick, and later a walking frame. I have seen her limp painfully and awkwardly carrying an entire roasting tray laden with meat and potatoes to the table using one hand and her zimmer frame at her old house in Spearwood. She was also renowned as a scone maker, which in a big, hungry family was a bonus, particularly for my late and great Uncle John who claimed to be able to “swallow a scone whole without biting it!” I have no idea how I happened to be the lucky recipient of this knowledge, but serendipitously I was at Spearwood when Granny was making scones and in the mood to share her recipe, which I have never forgotten. It is so easy, so economical and so satisfying!

4 (tea) cups of SR flour (super cheap)

2 oz butter (a tiny amount of the most expensive ingredient!)

Water to mix (hello-anyone can get hold of this!)

Preheat oven to HOT, rub butter into flour with your fingertips until it resembles breadcrumbs, mix in water until it’s sticky but not too wet (sorry, no exact amounts were given). Turn out immediately onto a floured board (DO NOT OVER-HANDLE). Pat lightly to a height of about 1 ½ inches, cut out with a glass if you don’t have a cutter, put on tray, sling into hot oven and cook until brown (approximately 10-15 minutes). That’s it!

This recipe has impressed one and all, from the firefighters hosing down yet another fire at my place, to my little Canadian friends who call me “Anty Gay” and who have helped me make numerous rounds of scones. I even have a photo of the results of this recipe from a kitchen in Glasgow, where my nephew and his wife knocked out a terrific batch, with added fruit for zing.

So Grannies one and all, your legacy is lasting, your influence is far-reaching and you will never be forgotten, as long as your words and your skills are still being used by anyone, even those you never met.

Owyergoinmateorright?

As a lonely Year 9-er, between friendship groups at a horrible girls’ school, I naturally spent a lot of time in the library at recess and lunch, trying to stay under the radar and avoid attention. I remember one of my many book companions at this time was “They’re a Weird Mob”, purportedly written by Nino Culotta a “new Australian”, but in actual fact the pen name of a bloke called John O’Grady. I found this book so screamingly funny that my efforts at invisibility were foiled, as I was shooshed and tutted at from all directions (by the grown ups, because the actual kids were out in the yard hanging out with real people.) Anyway, I hadn’t thought about that book for years, and whilst I am mostly grateful for the solace it provided for me at the time, lately I have been thinking more about the content and purpose of the book.

The novel, set in 1950’s Sydney describes the experiences of Nino Culotta, an Italian migrant who starts working with an ocker bricklaying team, Joe, Dennis, Pat and Jimmy, who he finds to be ‘strangely profane and cynical and abusive, but basically such good men, delighting in simple pleasures’. In keeping with the era, the book is sexist, racist and inappropriate, but the overall “vibe” is one of such affection and tolerance between these two sides that it really gave me a particular view about the value of migrants in general at a formative time of my life.

I remember feeling proud of how rude and funny and insensitive the Aussie blokes were, and feeling warm and fuzzy and satisfied when everybody had ultimately got a solid cross-culturally enriching experience by the end of the book. I identified with the Aussies but also with Nino, because the book kind of made it seem that there was nothing too weird about anyone, that couldn’t be embraced and absorbed and celebrated in Australia, this special place where really, everyone is welcome as long as someone brings the beer.

I guess that’s actually why, in today’s Border Force Australia, I’m not just feeling lefty-luvvy-latte-sipping outrage at the way things are going, what with the concentration camps and allowing young fellas to die of neglect on hot tarmacs and state-sanctioned abuse of kiddies and the like, but fear, real fear that the Australian identity, of which I was once so proud, has gone.

I think I am probably more baffled, puzzled and disappointed than anything else that the funny, irreverent, take-the-piss Australian character that I took as a part of my own identity has been replaced by this thin-lipped, snide, avaricious, insular, I’m-right-Jack person masquerading as my fellow countryman.

Come back Joe, Dennis, Pat and Jimmy-your country needs you.

Flying Limbs

In the work and task-driven life I have chosen, it’s been so easy to forget the importance of creativity and self-expression, so it was great having my creatively determined sister come down recently and spend the long weekend with me, with the express purpose of going to the Margaret River Readers’ and Writers’ Festival. I have been to this event a few times, but in the past couple of years had always found something more important to do, like mowing the lawn, getting wood, cleaning the house, cooking for the week ahead; in short, doing things that probably won’t feel very important on my deathbed, instead of taking some precious time to be inspired and refreshed.

We went to a poetry session, and listened to Dennis Haskell reading heart-wrenching poems he had written as his wife was dying from ovarian cancer. It was such a moving session, with the poet and much of the audience in tears throughout as Dennis read and spoke about his experiences.

I left the session so uplifted, and in such a different frame of mind, that it really got me thinking about those people who seek the creative path, whatever the cost. I had recently watched the movie “Still Alice”, which dealt with the tragedy of a woman diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s Disease at 50 years of age. She had three children: a son who was a doctor, a daughter who was a lawyer and a younger daughter who was a struggling actress. Before her illness, Alice had spent a lot of time fretting about this daughter’s lack of a “real job”, but as Alice’s memory deteriorated, it was the flaky daughter who was able to communicate most directly and fruitfully with her, really “meeting her where she was.” As a person who has spent the majority of my adult life endorsing, pursuing and attaining mainstream, conservative achievements, I was similarly bewildered by my son’s refusal to become a fine upstanding teacher; instead choosing to pursue a degree in art and illustration.

This is the sort of choice I would never dream of making, but that poetry session really made me reflect on what we lose when we spend no time at all on creativity. It worries me that we are sending children to school younger and younger, reducing the time spent on imaginative play and pushing 5 year olds into formal learning in the name of productivity.

In the spirit of creativity, I would like to share one of my poems that I wrote many years ago, and had completely forgotten about until I went to that writer’s session- I hope you enjoy it

Last Year at Home

Big brown eyes

Stands at the door

Looking out from safety

At his world.

Days stretch on and on

When will it all end for him?

And the world begin

To take away his open face

Open eyes

Open mouth

Flying limbs?

Sunrise, sunset

Thou art thy mother’s glass and she in thee

Calls back the lovely April of her prime

(William Shakespeare: Sonnet 3)

The passage of time: how commonplace, how relentless and, unless you die young, how totally unavoidable. There’s something about the transformative nature of time that I have always found so compelling, and sad/happy. Perhaps it’s just my Western cultural denial of death and decay, but I have always found the pace of change in myself and the people around me a bit disconcerting.

I was grabbing some after-work groceries a couple of evenings ago; it was cold outside, getting dark and the supermarket was busy and bit hassled as it always is at that time of day. I noticed a young couple near the vegie stands looking slightly harassed and getting tetchy with one another, and glanced again as they both looked a bit familiar. It wasn’t until they had passed me that I realised they had the grown-up versions of the faces of children that I knew. Living in a small town, you get to know which of your children’s schoolmates are dating whom, and for the first year or two after they all leave school, it all seems quite sweet and of course you expect them all to move to the city and meet other strangers and that’s that. There was something though about the body language between these two that told me that they were a totally established, long term, probably-thinking-about-getting-married couple, just like I had been, you know, a few years ago, but surely not so long ago that these primary school-aged children could have moved somehow into that spot …I mean, I realise that I’m not doing school lunches anymore, and maybe a couple of the “cool girls” from my year at school are now GRANDMOTHERS but, like, what’s happened here??!

I remember feeling the same way a couple of years ago when I first got onto Facebook and was able to connect with old school friends, some of whom I hadn’t seen since Year 12. I distinctly recall how strange it was seeing a picture of one of the guys with his son, who not only looked just like him, but was exactly the same age that my schoolmate had been the last time I saw him. It was such a peculiar Rip Van Winkel feeling, to be looking at the face of a familiar boy, knowing that the young fella I remembered was in fact the greying, middle-aged man standing next to him. What had happened to the boy I knew?

Living in a small town means that you get to see people born, learn to walk, have playdates with your own children, sing at assemblies, finish school, have their own babies and eventually become middle aged. You get to watch powerful community leaders and fearsome matriarchs weaken, lose their power and disappear from the committees and meetings and boards in which they played so vital a part, and which, at the time may have seemed impossible to run without them. You get to see, first hand, that nobody is indispensable, even if they feel irreplaceable, and you marvel that the PhD expert you now need to consult was someone you first met as he was pulled from his mother’s womb.

Having the opportunity to watch the effects of time within a small community is both disturbing and grounding. To see the waters close over other figures and to know that one day it will softly close over you as the life of the town flows on is healthy and humbling. The challenge is to try and live as George Bernard Shaw tells us:

This is the true joy in life, the being used for a purpose recognized by yourself as a mighty one; the being a force of nature instead of a feverish, selfish little clod of ailments and grievances complaining that the world will not devote itself to making you happy.

I am of the opinion that my life belongs to the whole community, and as long as I live it is my privilege to do for it whatever I can.

I want to be thoroughly used up when I die, for the harder I work the more I live. I rejoice in life for its own sake. Life is no “brief candle” for me. It is a sort of splendid torch which I have got hold of for the moment, and I want to make it burn as brightly as possible before handing it on to future generations.

It tolls for thee…

So I was riding my bike home from town the other day, along a quiet country backroad lined with huge karri trees, and I started to daydream, as I often do. Well, to be honest, not so much daydream, but fall into the type of imaginings I had as a child, when I used to love playing various daring roles with my sisters.

I was lucky enough to be raised in a very large family of (mostly) girls, with one long-suffering brother, and the best thing about this was that you never had to scratch around for someone to play with, or for something to do. We were all very avid readers as well, and having had both parents in the armed forces in WWII, quite a few of our games involved complicated escaping-the-Nazis-French-Resistance storylines, with ourselves cast in heroic roles-always the good guys. These adventures were always spiced up whenever we could convince our brother (generally as the bad guy) to join us, because he had awesome “cap guns”, you know, the ones that made a sharp cracking sound and puffed out a little bit of smoke when you pulled the trigger. You can probably still get them in Bali I imagine…

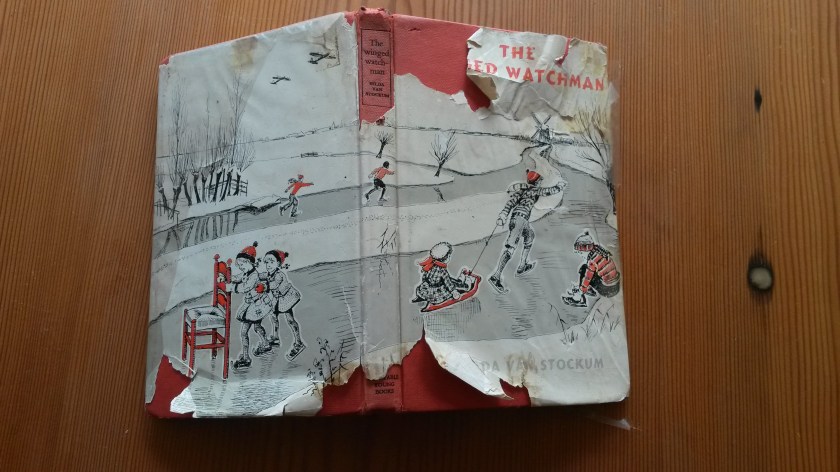

One of my favourite books that I read and re-read (even as an adult) was a Dutch novel called “The Winged Watchman” by Hilda Van Stockum. The story is told through the eyes of Joris Verhagen, a 10 year old boy who lives in a windmill with his parents, older brother Dirk Jan and baby sister Trixie, and it deals with their lives under Nazi occupation. In one scene, a young girl, Reina, who is working for the Dutch resistance, is cycling along with a satchel full of forbidden newspapers, when she is accosted by a Nazi collaborator, who demands that she get off her bike, then throws her onto the side of the road. Bicycles, at that time, were no longer available to ordinary people, and the thug is outraged when he sees Reina coolly ignoring the interdiction and deals with her accordingly. Although Reina lives to tell the tale, the frightening incident sets a super-suspenseful mood for the novel.

So, occasionally, when I am riding along freely, breathing sweet country air, listening to the sound of the birds and occasionally waving to an acquaintance, I get a scary thought about what it would be like to be in a situation like Reina. To be listening out for the sound of drones, or gunfire, or to be looking over my shoulder, and I feel, for the millionth time, how incredibly lucky I am to live in such a peaceful and safe place, and feel so sad for those many millions of faceless and nameless people who don’t.

They’re not all faceless though. I am in touch with a young Rohingya chap on Manus Island, who’s been there in a mouldy tent for nearly three years. For those of you who don’t know, the Rohingya are possibly the most persecuted group in the world. An ethnic minority in Burma for generations, the Rohingya are unable to be citizens of Burma. Ever. Even the peace-loving Buddhist monks there won’t have a bar of them, and the much celebrated freedom fighter Aung San Suu Kyi has turned her back on them, needing the support of the military establishment there to shore up her fragile fledgling democracy. And I guess I kind of get that, I mean, maybe the end does justify the means and God knows I have never had to be in the position to make huge decisions like that, and maybe it’s easy to criticise when I will never have those responsibilities. But I don’t know.

I do know that it makes me sad to reflect that it’s a lot harder these days, for me to think of Australia, this land that I love so much, as one of the good guys.

A poem I often think of when I am corresponding with a few of the young fellas on Manus and Nauru is John Donne’s No Man is an Island, but I think this short passage from the Winged Watchman sums it up pretty well. After liberation, Joris’ mother is speaking to a Jewish woman who was the sole surviving member of her family and says to her: “how you must hate the Germans!”

But Mrs Groen shook her head. “Oh no” she said. “I’m sorry for them. To suffer yourself, that is nothing. God will wipe all tears from our eyes. But to hear God ask: ‘Where is your brother?’-that must be dreadful. The hardest to bear are the wrongs we do others.”

Wishing all of our politicians the strength and courage to remember for whom the bell tolls. .

Mmmm…stillness…

I’m not sure when this poem started running around in my head, but given the week I’m having, the lure of stillness and silence feels very compelling…

It was written by the English poet, Gerard Manley Hopkins, who, in addition to being a Jesuit priest , (don’t let that put you off) wrote some of the most beautiful, exquisitely crafted poetry you will ever read.

Hopkins’ style was unique in that he used non-traditional rhythms, making his poetry fresh and sparkling. He often created words, as though the English language was not big enough to express what he saw and experienced.

The title of this poem “The Habit of Perfection” is a play on the double meaning of a “habit” as a daily practice as well as the donning of the habit of religion. I particularly love his description of the silence he has chosen, or “elected” beating “upon (his) whorled ear”, just one of the many acute observations of nature’s replications in the shell-like “whorls” in the human ear.

Having just spent some time in India, I was fascinated by the dozens of religious traditions there, and although the motifs and symbols in this poem come from the Christian tradition, the ideas of seclusion, silence, fasting and the inward journey are common to all traditions. I hope you enjoy it!

The Habit of Perfection

Elected Silence, sing to me

And beat upon my whorlèd ear,

Pipe me to pastures still and be

The music that I care to hear.

Shape nothing, lips; be lovely-dumb:

It is the shut, the curfew sent

From there where all surrenders come

Which only makes you eloquent.

Be shellèd, eyes, with double dark

And find the uncreated light:

This ruck and reel which you remark

Coils, keeps, and teases simple sight.

Palate, the hutch of tasty lust,

Desire not to be rinsed with wine:

The can must be so sweet, the crust

So fresh that come in fasts divine!

Nostrils, your careless breath that spend

Upon the stir and keep of pride,

What relish shall the censers send

Along the sanctuary side!

O feel-of-primrose hands, O feet

That want the yield of plushy sward,

But you shall walk the golden street

And you unhouse and house the Lord.

And, Poverty, be thou the bride

And now the marriage feast begun,

And lily-coloured clothes provide

Your spouse not laboured-at nor spun.

Little Legacy

I was absent-mindedly making an origami boat as I quite often when I am forced to sit still and endure something boring, but want but really need to be productive (Enneagram Alert-“3” wing!) and it struck me how my ability to do this was thanks to a family friend called Aatso.

Aatso was a “new Australian” from Estonia who was part of our family for a few years during the 70’s. My Dad is a renowned lame duck gatherer whose lifelong compassion has led him to unreservedly support vagrants, wastrels and ne’er do weels of all kinds, frequently giving more than he can afford and extending chance after chance in repeated triumphs of hope over experience.

Aatso was certainly not a wastrel or time waster though. He was a young teacher that Dad had met at his workplace. He had no family here- they were all stuck back in Estonia in bread queues. He had had an horrific time during the war, drafted by the Nazis into the SS-it was never openly spoken about but we were all told about it at some time.

Aatso’s English was very good, although he had a pretty strong accent. Being the 70’s, we were, of course, totally unashamed about mocking foreigners of any kind, although at least we were polite enough not to do it to his face. He was very kind to us-there were six kids: five girls, one boy and most of our time with Aatso was spent at the holiday house in Gracetown that dad had built during his holidays from TAFE. There was a much bigger generation gap between children and adults in those days, so of course we kids had our own world and the adults had theirs. Aatso seemed much younger than our parents, but was just another adult to us, and a slightly weird one at that.

However Aatso had some great tricks that other adults didn’t have-he was an amazing gadget inventor-like a mad scientist guy, who was always making little things that could help with life’s little problems. He created a specialised fly switch from fishing line-a perfectly braided and corded lightweight switch that you flicked side to side over your shoulder as you walked to the beach. We were used to flies of course, but he was appalled by the inconvenience, so found an elegant and perfectly formed solution. He was mad on fishing which Dad had introduced him to, so had invented a sort of lure/berley cage thingo that got those herring really boiling.

When it was raining though, he introduced us all to origami and string figures. My little sister Pip sat practising “apache door” for hours until she had mastered the difficult string figure-we all got to learn it, and as 8 ,9 and 11 year olds my two nearest sisters and I would have races to see who could complete Apache Door in the least time. The other trick Aatso taught us was how to make a perfect origami boat that really floats. It’s such a neat, awesome little thing, that turns itself inside out at the last step to reveal a perfectly proportioned boat and I have never forgotten how to make it.

Aatso never married or had children, and spent many years in analysis, trying to come to terms with the horrors of his past during the war. He died of cancer quite young. I will always remember visiting him in hospital when he was dying. I was about 13 and had never seen anyone so skeletal. The wig he was wearing only added to the sense of tragedy. I guess it might not seem like much of a legacy to leave, but every time I fold a square of paper to make that boat, I always think of Aatso, a brave and haunted man, who spent endless hours with a bunch of annoying and noisy kids carefully and patiently showing us how to create a little piece of perfect craft.

Anzac Reflections

I always feel torn about Anzac Day. God knows I want to join with everybody else on Facebook, posting poppies and pictures of long-dead relatives, sent far away by the Empire and sacrificed for a few metres of rocky ground in a foreign land.

I always feel torn about Anzac Day. God knows I want to join with everybody else on Facebook, posting poppies and pictures of long-dead relatives, sent far away by the Empire and sacrificed for a few metres of rocky ground in a foreign land.

As the daughter of two WWII veterans, and the grand-daughter of a WWI decorated hero, Anzac Day was always a special day in our house when I was a child. A bit like Good Friday, it was a sad day, a sombre day where we always put the march on TV, and watched to see if we could catch a glimpse of one of our friends or relatives marching. We weren’t really Dawn Service people, although I think my parents used to go along before they had all of us to slow them down.

Our great uncle Johnny Mountjoy was one of the original Anzacs, killed at Gallipoli, and family legend has it that his mother saw him lying “black and dead” in her dreams long before she received the news of his death. Johnny’s brothers also served, and bore the mental scars their whole lives, coming home to live on a street in the Upper Swan which our family referred to thereafter as “shellshock corner.”

My maternal grandfather Geordie Mulligan enlisted in the AIF in 1915 at the age of 17 (he fibbed about his age), was wounded twice and returned to the front both times, awarded the Military Medal for “ bravery and devotion despite personal danger” at Anzac Ridge, and spent 9 months in a German POW camp before finally being repatriated back to Australia in 1919. As if this service was not enough, he enlisted again in WWII as a sergeant from 1941-45, when he was finally discharged from the armed forces at the end of the war.

I think it’s fair to say there’s a solid Anzac pedigree in my family, yet my struggle with the “celebration” that the day has now become, persists. I feel great pride, but also great fear when I see the increasingly overt symbols of jingoistic patriotism displayed on the day. The great WWI poet Wilfred Owen served on the Western Front, was awarded the Military Cross and was killed in action a week before the Armistice was signed. No one could have had a greater entitlement to comment on that war, and his haunting words as he describes a gas attack leave us with a message we do well to remember:

“If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie; *Dulce et Decorum est

Pro patria mori”

*Sweet and proper it is to die for the Fatherland

Lest We Forget