I’ve been feeling quite bucket-listy since my 60th birthday, with a turbo-charged drive to complete unfinished things. So, last May I set off for the USA with one of my many sisters, to visit the home of Laura Ingalls Wilder-a favourite childhood writer of ours.

We were a bit nervous even then, about what to expect at US Customs, and had removed all our social media accounts before getting to Honolulu. I’d even dug through my search history and deleted everything remotely anti-orange, just in case. I shouldn’t have been surprised that two chubby, old white women would be waved through security with barely a glance, but the relief was enormous once we were released into the soft Hawaiian daylight.

Refreshed after a couple of nights at Waikiki beach, we flew to South Dakota to pick up our hire tank (sorry, car) at Sioux Falls airport. I had to go back into the Hertz office to ask the man how to start it because I didn’t know that you could start a car without a key. Oh, how I longed for my 25-year-old Commodore. “Stay right!!!”, my sister yelled, as I veered out of the carpark on the wrong side of the road, making our sweaty, cortisol-fuelled way to the cute Air BnB.

Sioux Falls is a quaint mid-western town, and we were enchanted by the doll-house homes, squirrels and lovely gardens as we wandered around to get our bearings. True country-bumpkins, we stopped to chat to a young bloke who was digging out a stump on his verge. His wife came out, and introduced herself to us as Ottam, and I’m so glad that instead of commenting with my usual gaucherie on her unique, perhaps Arabic? name, I asked her to spell it out for me: A-u-t-u-m-n. “Oh Orrrrddum!” I drawled before we scurried away to find a shop where milk didn’t cost $4 AUD a litre. Walmart was a revelation, and we took photos of all the weird food. There was bison in the meat fridge and the cheese was orange. We weren’t sure if that was a political decision on the part of the supermarket, but it didn’t look like it had come from a cow, so we stuck to eggs, bread and yogurt. Even with our unfavourable exchange rate though, it was clear that people were paying about 50% more for groceries than we were at home. We felt a bit sorry for them, especially considering their low minimum wage and no healthcare situation, but we didn’t like to say it out loud.

Our time at Laura Ingalls Wilder’s hometown of De Smet was everything we hoped for – a real dream come true. My most treasured memory was sitting at the De Smet cemetery in the soft sunshine, with the breeze whooshing quietly through the pines and little birds chirping as they would have done for thousands of years. I really felt a connection to Laura, and to all the people who had lived in that place.

Despite our nostalgic memories of reading the books as children, seeing them now with post-colonial eyes did make the experience bitter-sweet, but a bit more realistic. We bought several good texts including the Pulitzer Prize winning “Prairie Fires” and the impeccably researched “Little House, Long Shadow” (see links at the bottom).

These gave us heaps of context around the true cost of our heroine’s journey on the indigenous people of the Great Plains, and the cultural and environmental destruction that followed in the wake of white settlement. These books also started to explain to us the dogged American obsession with independence, even when it results in extreme personal disadvantage. Laura’s daughter Rose Wilder Lane was also a well-known writer, and a famous libertarian, and her opposition to the government’s help during the Great Depression was completely baffling and idiotic to our Australian minds. Why would anybody rather starve than depend on the government for a short while? It all helped to build our understanding of this huge and complex country, because we needed all the explanations we could get once we hit New York.

I know that Gossip Girl and Sex and the City aren’t real, but the contrast between the New York of these shows and the drab, depressing and desperate city that we found was incredible. The dirty streets, uncollected rubbish and neglected parks were nothing compared to the filthy dystopia of the subway. The only place I had ever seen dirtier than this was Varanasi in India, but the streets there are crowded with pigs, cows, goats, dogs, donkeys and camels, all shitting at will, so at least the filth made sense. We longed to take a pressure hose to the platforms, with industrial-strength detergent and a scrubbing brush. Our accommodation was in a Hispanic part of Brooklyn, where locals told of tales of disappeared neighbours and spoke of the fear that was rippling through the area. People were friendly and warm, just like they were in the mid-west, but the daily struggle of everyday life was obvious, and we had already been scandalised at the price of groceries in South Dakota. By contrast, we visited relatives in Connecticut, about 40 minutes away, which was fairytale beautiful- all emerald lawns, quaint white weatherboard houses and masses of azaleas. The difference was jarring.

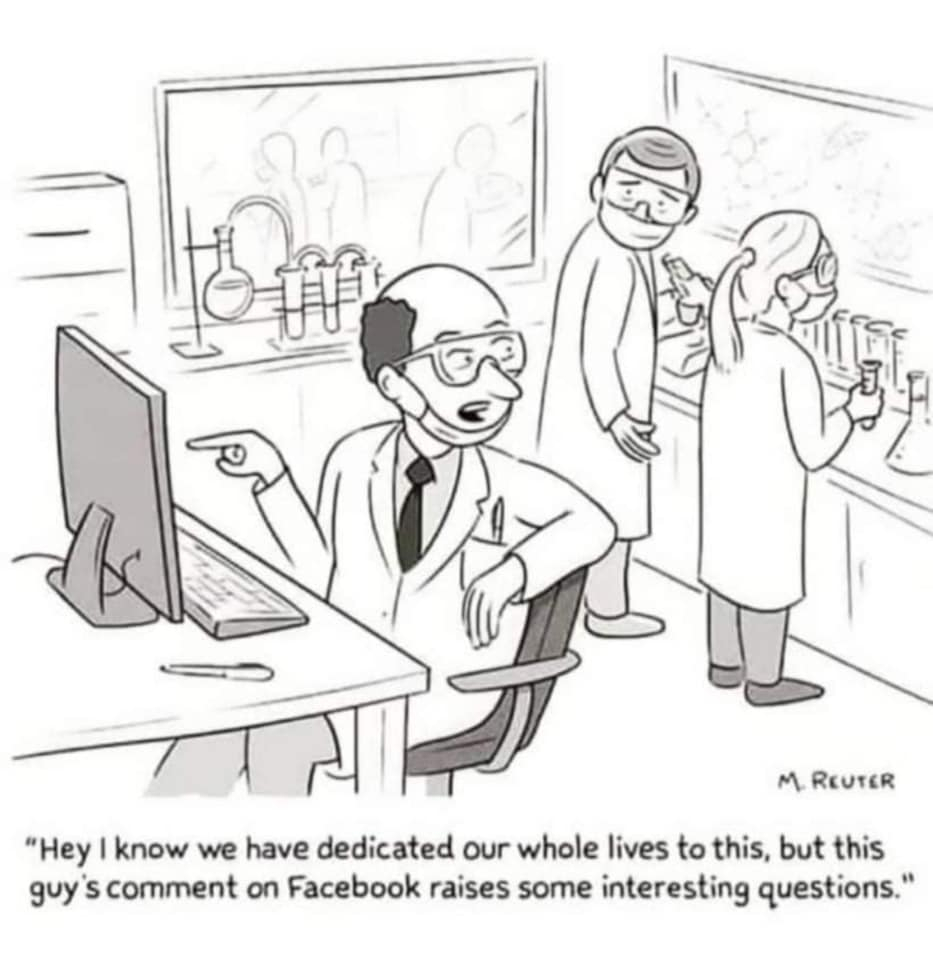

Before I visited the US, I had been scornful about the American peoples’ stupidity in twice electing a brazenly dishonest, abusive grifter as president, but my time in the States gave me a better understanding of how this had happened. It was quite clear to us that America was not great and probably hadn’t been great for a long time. The disparity between rich and poor, the resignation to neglected streets, fetid subways, meagre public services and non-existent healthcare must grind people down to the point where nothing really matters. Like a battered woman without hope, America is a country entrapped in a system so violently skewed to bolster the rich at the expense of the poor that it is hard for many people to think beyond daily survival. In this reality, a vote for the loudest voice that promised anything different was an electric shock which momentarily aroused the population from numbed inertia. That Trump promised not merely a continuation of the same, but an escalation of harm makes the decision more staggering. Further abuse and neglect of already disadvantaged communities, the slashing of poorly resourced services and a gleeful removal of constraints on open racism and discrimination was all promised and is now being delivered. In a society without any expectation of meaningful change, it is perhaps unsurprising that voters abandoned any pretence of decency and placed their faith in disruption, however ruinous. In fact, given what we saw in the States, it is a testament to the resilience of the American people that they haven’t descended to this level before now. I realise that this sounds condescending, and maybe it is, but it’s very hard to understand how the “greatest country on earth” can continue to accept this level of social, educational, health and community neglect. Some Australians like to flirt with the idea of “stopping socialism” in our country, but try taking away their Medicare, liveable wages, public hospitals, schools, child health clinics and PBS medicines and see how anti-socialist they really are. These are things that Americans can only dream of yet continue to willingly trade away in the name of “freedom”. It is galling to see similar notions of aggressive individualism start to creep into Australian discourse, via hard right political movements. Such ideas are the antithesis of the “Australian values” these movements purport to hold dear, and are genuinely unwelcome, foreign imports.

There were nice things in New York too. We went to the Moma Gallery and saw Van Gogh’s “Starry Night”, and the Metropolitan Museum was just gorgeous. It was a thrill seeing the Statue of Liberty, and the fascinating immigration museum, which honours the courage and contribution of the many migrants who have made America their home. Also, most people were very nice, contrary to what we had heard about New Yorkers.

It was a relief to get to Canada though, which felt like home, just colder and with a lot of ice-hockey on TV. The subways were clean, and they had proper food that had once come from a plant or animal. We stayed in beautiful Charlottetown and visited Green Gables which was delightful. I found my brain had adjusted to driving on the wrong side of the road after a few days, but I never could get the hang of crossroads where all sides had a stop sign. I just lay there doggo, hoping that someone else would win this game of chicken for me, but I never did find out who was supposed to go first.

https://littlehouseontheprairie.com/little-house-long-shadow/